Long-term emotional consequences of parental alienation exposure in children of divorced parents: A systematic review

Current Psychology volume 42, pages12055–12069 (2023)

Abstract

Although the emotional consequences of childhood exposure to parental alienation behaviors in children and adolescents of divorced parents are known, there is scarce evidence on their long-term consequences in adulthood. Therefore, this work aims to conduct a systematic review of the state of research in this area and its main conclusions and identify gaps and limitations to guide future research. A search of the literature was performed in electronic databases PsycInfo, MEDLINE, SCOPUS, Web of Science, PubMed, Cochrane Library, DART-Europe, ProQuest, Wiley, TESEO and Dialnet, and a secondary review of the bibliography; in February 2019 updated in December of the same year. Thirteen pieces of research were selected after applying inclusion and exclusion criteria; twelve published articles from journals and one doctoral thesis, both with qualitative and quantitative methodology. Children exposed to parental interference and alienation show in adulthood depression and anxiety symptoms, a higher risk of psychopathology, lower self-esteem and self-sufficiency. As well as, higher alcohol and drug use rates, parental relationship difficulties, insecure attachment, lower life quality, higher divorce rates, feelings of loss, abandonment and guilt. They also report repetition of these alienating behaviors on their children by their partner or their own children’s grandparents. Some limitations of the study are described, and proposals are made for future research.

Introduction

The family is a system, and its members affect and are affected by family processes, as is the case with inter-parental conflict (Cummings et al., 2016). Such conflicts can be constructive with minimal negative effect and fulfill a protective role in family functioning; or can be destructive, characterized by an unwillingness to resolve conflict, large hostility, defensiveness, withdrawal, a threat to family integrity, or violence and physical aggression (Zemp et al., 2016). These latter conflicts have significant effects on children´s development due to both direct and indirect exposure as well, such as changes in parenting and family relationships (Cumming and Davies, 2010), divorce (Martínez-Pampliega et al., 2015), parental depression (Wishman, 2001), parental alcoholism (Cumming & Davies, 2010); or physical, emotional and sexual abuse (Sturge-Apple et al., 2012).

As mentioned above, inter-parental conflict increases divorce risk and, therefore, couple dysfunction (Bodenmann, 2005). A couple’s breakup does not mean conflict is finished, as a new scenario appears where the dispute is perpetuated. Moran et al. (2015) indicate that in 20–25% of divorces, parents show a high conflict co-parenting relationship, characterized by poor communication, little cooperation, large mistrust, and disagreement in decision making. In this scenario, receiving child unconditional support can become the main aim. Parents can involve children in their disputes, using the child as a messenger and confidant about problems with the other parent, or even as an ally in the conflict (Camisasca et al., 2019). In this sense, Borszomengy-Nagy and Spark (1973) coin the term conflict of loyalty to describe the family dynamic where loyalty to one parent necessarily implies disloyalty to the other. While the child rejects one parent and feels devoted to the other (split loyalty). Similarly, Johnston and Campbell (1988) describe this loyalty process as alignment limiting contact with a parent, but without complete rejection and tending to show feelings of ambivalence (anger, sadness, love) (Johnston, 2003).

Buchanan and Waizenhofer (2016) report parents can use children to feed their tension (triangulation), focusing on the child as the source of their problems (scapegoat) or implicitly or explicitly pressing the child to take sides in the conflict. Children may resist this pressure, either by emotional distancing from parents or trying to keep a balanced affective relationship with both. Resulting in children feeling trapped in the center of the conflict, which can trigger a conflict of loyalty in them. However, if they yield to pressure and take sides, alignment occurs, causing anger, disconnection, and rejection toward the other parent. Similarly, Kelly and Johnston (2001) state that after separation or divorce, parent–child relationships can be conceptualized along a continuum, from positive to negative: from establishing positive relationships with both, followed by greater affinity with one parent while maintaining contact and a relationship with the other, creating alliances with one parent and distancing for justified reasons and, lastly, on the extreme negative end of the continuum, alienation of the child. According to these authors, alienation commonly occurs in high conflict divorces, the child expressing intense rejection of and resisting contact with one parent, showing no apparent guilt or ambivalence.

Although this phenomenon has been conceptualized in different ways throughout the research (“malicious parent syndrome associated with divorce,” Turkat, 2002; “threatened mother syndrome,” Klass & Klass, 2005), the best known is Parental Alienation Syndrome (PAS), coined by Gardner in 1992. This author describes the main symptoms in children affected by the syndrome: denigration campaign, weak or unjustified reasons to scorn the parent and not wishing to be in their presence, “independent thinker” phenomenon, unconditional loyalty to the alienating parent, indifference to the feelings of the rejected parent, borrowed arguments, and extension of animosity towards the rejected parent’s extended family and social network. Waldron and Joanis (1996) odd contradictions in children’s statements, knowledge of inappropriate and unnecessary information of the breakup, and the legal procedure or restriction of their permission to love or be loved. In Spain, parental interference is described as behaviors, strategies or actions that parents deploy to hinder and damage the relationship with the other parent, understanding Parental Alienation (PA) as a result of these actions on the minor and in their relationship with the parent who is the target of alienation (González, 2019); i.e., the maximum expression of parental interference would be PA, characterized by loss of contact with and rejection of the parent.

Extensive literature shows parental interference and PA can occur both in intact and non-intact families (Baker & Chambers, 2011; Baker & Verrocchio, 2013, 2015; Verrocchio et al., 2019), triggering inter-parental conflict, divorce usually aggravates this situation, presenting a greater number of more frequent and intense alienating behaviors regardless which parent engages in them (Baker & Verrocchio, 2013, 2015). Even when PA does not occur, parental interference harms both alienated parent and child (Harman et al., 2018), causing negative psychological effects (depression, anxiety, etc.), educational level (impaired educational performance, school dropout), legal (time, cost), and physical (hypertension, etc.) (Harman & Biringen, 2016). In a systematic review of the literature, Maturana et al. (2018) report that the target parent, focus of the alienation, suffers emotional, psychological and economic effects. They experience dissatisfaction with legal and mental health systems. Depressive and anxiety symptoms and high trauma levels have been verified, with parents perceiving a highly threatening and stressful situation (Balmer et al., 2017; Harman et al., 2019).

Parental alienation can cause permanent psychological damage to children and is, therefore, considered emotional abuse (Gardner, 2006; Harman et al., 2018). In adults exposed in their childhood to their parents’ divorce, in particular, research shows the linkage between PA exposure to and psychological abuse by the alienating parent. This indicates that regardless of parental gender, the greater number of strategies deployed, the higher the score on the psychological abuse scale is (Baker & Ben-Ami, 2011; Baker & Verrocchio, 2013, 2015). Another variable related to these PA strategies is parental care, parents showing lower care rates and increased overprotection, all of which are reflected in acts of omission (isolation and denial of emotional response capacity) and acts of commission (rejection, terrorize and exploit) (Baker & Verrocchio, 2015). According to Verrocchio et al. (2015), this means empirical confirmation of the theoretical definition of parental alienation, lack of empathy, and inability to tolerate the child’s needs and perceptions different from their own. Encouraging disobedience in children, blaming the other parent for their behavior or belittling the other parent in the child’s presence, sharing excessive information with the child, and promoting parentification are all behaviors involving low parental care and hyper control over children.

For children exposed to these dysfunctional relational dynamics, consequences may manifest in the medium, short, or long terms. According to various studies, during childhood and adolescence, symptoms linked to PA are anger, guilt, hostility, impulse control problems, low self-confidence and self-esteem, anxiety, depression, phobias, sleep disorders, suicidal ideation, problems in personal and social relationships, identity and image disorders, personality disorders, substance abuse, decreased academic performance (Fidler & Bala, 2010; Gardner, 1992; Johnston, 2005; Lowenstein, 2007; Sher, 2015; Stoner-Moskowitz, 1998). Likewise, children can maintain and/or develop consequences throughout adulthood, consolidating long-term affectation, with interference in development at work, social and psychological levels, hindering the establishment and consolidation of partner relationships, and so forth.

Due to the serious life implications of these children, several research has been conducted in recent decades on the emotional consequences in childhood and adolescence of exposure to parental alienation behaviors in children of divorced parents. However, there is scarce evidence of the implications of such exposure during childhood in adult children (long-term consequences). This systematic review of the literature was performed seeking evidence on the psychological and emotional consequences in adults who have been exposed to parental divorce and parental alienation during childhood, as well as identify underexplored variables and identify gaps to guide future research.

Method

This systematic review combines information from articles that include the study of parental interference in children of divorce in adulthood. The PRISMA verification protocol is used for correct development and presentation of meta-analyses and systematic reviews (Moher et al., 2009).

Search Strategy

We performed a search of the literature in the following electronic databases PsycInfo, MEDLINE, SCOPUS, Web of Science, PubMed, Cochrane Library, DART-Europe, ProQuest, Wiley, TESEO and Dialnet, and a bibliographical review of articles to select potential studies. The following terms are used: [(“parental alienation” OR “parental interference”) AND (divorce OR separation OR “parental separation” OR “break up”) AND (adult OR “adult children” OR “young adult”)]. The search was carried out between February 1 and 14, 2019, updated from December 15 to 30. The study selection process was carried out by one reviewer.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The studies included in the current review have met the following criteria: (a) published articles or doctoral theses, published and unpublished, which include the study of the emotional consequences in adults of parental interference that occurred during childhood of the children of divorced parents (b) the studies must include, as independent variable, a measure of parental alienation, c) researches that include, as dependent variable, at least, a measure of adult functioning or emotional distress (as emotional well-being or psychopathology); and d) participants should be aged between 18 and 40.

However, books, reviews and literature reviews were excluded, and also articles whose title or summary that did not include search terms and/or referred to related but not directly linked subjects, as well as those not including the study of psychological variables associated with parental alienation behaviors experienced in childhood. Finally, articles not written in English or Spanish are not included in this review.

Data coding and extraction

A data extraction sheet was prepared to extract and encode the most relevant information from each document in the review. The most important study characteristics are shown in Tables 1 and 2, country, study design, total sample, the number of participants in the total sample with divorced or separated parents, and participant characteristics. In addition, detailed information on variables considered in the study and measurement instruments used are included. Regarding empirical or quantitative studies, information on study aims, measuring instruments for parental alienation, instruments for psychological variables studied, and main findings are included. As for qualitative studies, the subject of interest, focus of qualitative studies, synthesis results, and strategy details are collected. Data extraction was performed by the first author (PM) confirmed by a second (CG) and third rater (MDH). Any discrepancies were resolved by consensus. As a final step, a data check presented in the review was conducted.

Results

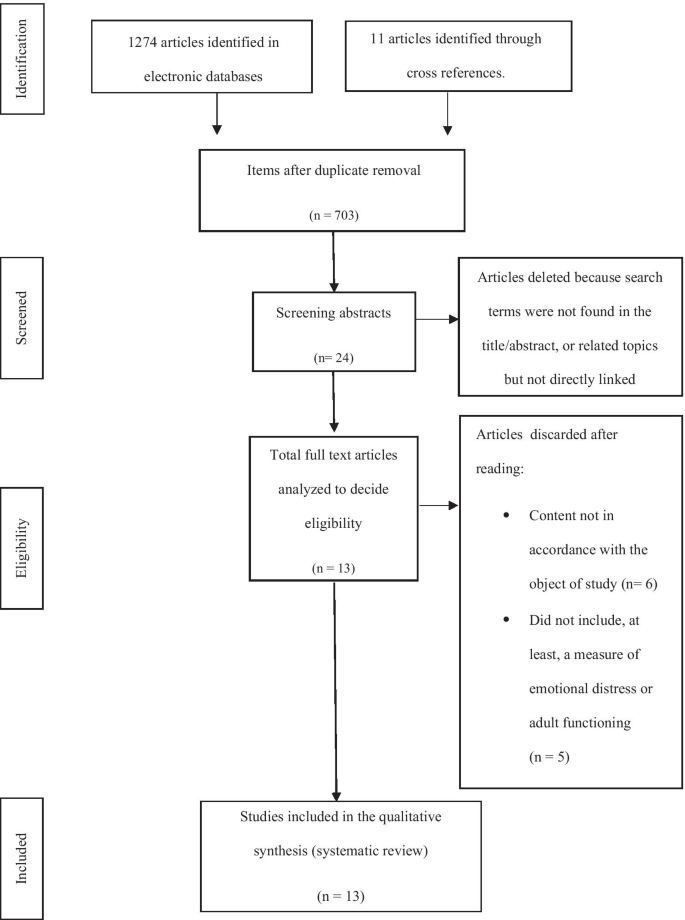

There are 1284 articles, 1274 identified in various databases and another 11 results from the cross-reference search. After removal of duplicates and application of inclusion and exclusion criteria, 24 articles were selected for reading. Of this, 11 were removed for not adapting content to the aim of the review. Thirteen articles were finally selected: 12 published in journals and a doctoral thesis. Article selection stages are broken down in Fig. 1.

Study characteristics

We summarize the main study characteristics in this review (see Tables 1 and 2). As observed, research on the adult population, PA’s focus was carried out in the last fifteen years; therefore, we face a problem in an emerging area of study. There are variations in sample size among studies, between 6 and 739 participants. All had more women than men, approximately 65% of the total sample, with no data on participant gender in two studies. The study sample’s mean age is between 24 and 40, the mean age of the total research sample 29.87, with only one study not including information on participant age. Three articles provide data on years since divorce at the time of research. Studies were carried out in the USA and Italy, except one realized in Canada, finding no research with a study population from other countries. The study methodology is mainly quantitative in eleven of thirteen articles, with another two following qualitative methodology. In nine articles, the sample comprises individuals with intact and non-intact families; in two, the number of participants from each marital status was not provided. The remaining four pieces of research in the sample included only those whose parents were divorced.

Regarding measurement instruments for parental alienation, the Baker Strategies Questionnaire (BSQ; Baker & Chambers, 2011) was mainly used, and the Parental Alienation Syndrome Questionnaire (PASQ; Machuca, 2005) was administered in one piece of research and the Parental Denigration Scale (PDS; Rowen & Emery, 2014) in one work involving a specific aspect of PA, the denigration campaign. Therefore, we considered its inclusion in the systematic review of value. The BSQ is developed by Baker and Chambers (2011), comprising 20 Likert-type items on parental alienation behaviors displayed by parents during the evaluated subject’s growth and /or development stage. Finally, a wide range of questionnaires is found among research for studying psychological variables due to the diversity of variables and the selection of measuring instruments for a given variable.

Emotional and psychological consequences

We conducted this systematic review to identify and synthesize information in the literature on parental alienation’s emotional and psychological consequences in children of divorced parents during adulthood. Thirteen articles were selected after applying inclusion and exclusion criteria, with twelve offering parental alienation measures and another article for a specific phenomenon within the process of parental alienation-denigration campaign (Rowen & Emery, 2019). Two pieces of research used a qualitative methodology, where the experience of alienation is described, as well as perceptions of the effects of exposure to these behaviors and about divorce (Baker, 2005; Godbout & Parent, 2012); while the other articles implement quantitative methodology.

Affective disorders

The vast majority of quantitative articles offer measures related to affective disorders. Eight for depression, assessed through the Inventory to Diagnose Depression Lifetime Version (IDDL; Zimmerman & Coryell, 1987), Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II; Beck et al., 1996) and Center of Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale for Adults (CES-D; Radloff, 1977); and three for anxiety. Study results generally show a significant link between exposure to PA in childhood and higher depression levels in adulthood, except for Baker and Chambers (2011), which did not find this relationship statistically significant. Regarding participant gender and the parent engaging in parental alienation, Baker and Verrocchio (2016) found higher depression scores in men reporting exposure regardless of the gender of the parent who performed these actions. In women, PA by mothers increases depression scores, being insignificant regarding the father. However, they state these results are simply due to exposure to parental alienation behaviors and not parents´ marital status, a result shared by Verrocchio et al. (2019). Parental denigration is also linked to higher levels of depressive symptoms, regardless of parents’ marital status (Rowen & Emery, 2019). In specific samples of subjects with divorced parents, Ben-Ami and Baker (2012) find participants exposed to these strategies have more probably to comply DSM criteria for Major Depression than those not exposed. In research by Baker (2005), most (70%) report significant episodes of depression in adulthood, believing symptoms are linked to early feelings of being unloved by the target parent of alienation and their current separation or lack of relationship.

As for anxiety, there are no studies with an exclusive sample of children of divorced parents. Only two articles refer to the measurement of anxiety connected to exposure to parental alienation behaviors (Baker & Verrocchio, 2016; Verrocchio et al., 2016). Both of them report that exposure of alienation behaviours (ABs) is associated with anxiety. Baker and Verrocchio (2016) report high levels of state and trait anxiety in men and women, regardless of the gender of the parent engaging in these behaviors (except for state anxiety, in the case of women and their exposure to PA by the mother), compared to those not exposed. Controlled for parental marital status, authors indicate that the rise in state and trait anxiety scores in both genders is due to childhood exposure to PA. According to Rowen and Emery (2019), denigration does not significantly correlate with anxiety symptoms assessed through the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI; Spielberger et al., 1970).

Psychological general distress

Three studies offer measures for this variable, one through the Symptom Checklist-90 test (SCL-90; Derogatis et al., 1973), the other based on its revised version Symptom Checklist-90 Review (SCL- 90-R; Derogatis, 1977), and another of its abbreviated version Symptom Assessment-45 Questionnaire (SA-45; Davison et al., 1997). Research shows that adults exposed to parental interference in childhood and experienced parental divorce have a greater risk of psychological distress (Bernet et al., 2015; Reay, 2007; Verrocchio et al., 2015). According to this, significant differences in SA-45 scores are seen among groups of adults from divorced families exposed to various degrees of parental interference compared to those not exposed (five groups: never, minimally, occasionally, often, most of the time) (Reay, 2007). The more often parents engaged in these behaviors, the higher the score on scales and, thus, the larger presence of psychopathological symptoms. Along the same line, Verrocchio et al. (2015) indicate that these behaviors and low self-esteem increase probability of psychopathological symptoms. Similarly, Bernet et al. (2015) state those whose parents are divorced/separated and report exposure to parental alienation score higher on most SCL-90 scales, with no differences found in the intensity of phobic anxiety scale for those who report from intact and non-intact families. In both groups, the more alienating behaviors suffered, the higher the scores on the questionnaire.

Self-esteem and self-sufficiency

The negative effects of PA extend to self-esteem and self-sufficiency. Five studies have measures for self-esteem and only one for self-sufficiency. Results show low scores on the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (RSE; Rosenberg, 1965) in adults of divorced parents exposed to these behaviors (Baker &Chambers, 2011; Baker &Ben-Ami, 2011; Ben-Ami & Baker, 2012; Baker & Verrocchio, 2013; Verrocchio et al., 2015). In this sense, Baker (2005) indicates that adults reporting low self-esteem express this result due to internalized hatred toward the parent and guilt and self-hatred for rejection of them. As for self-sufficiency, a higher score in BSQ was linked to a lower score in this variable, specifically assessing unemployment and educational level (Baker & Ben-Ami, 2011).

Alcohol abuse and drug use

Four articles study alcohol consumption in adulthood after parental divorce and PA exposure, using the CAGE questionnaire (Cut-Annoyed-Guilty-Eye; Ewing, 1984). A single quantitative methodological study finds a relationship between these variables. Baker and Verrocchio (2013) point out that exposure to PA by either parent following divorce correlated with alcohol abuse in adulthood, unlike the group not exposed. In this same direction, Baker (2005) reports a third of participants had alcohol problems and/or major drug consumption at some point in life, often in late adolescence and early adulthood. All this noting as an escape route from feelings of loss of relationship with the targeted parent and suffering due to low self-esteem and inter-parental conflict. In other articles that studied this variable, no significant differences were found in alcohol consumption between exposed and unexposed groups (Baker & Ben-Ami, 2011; Ben-Ami & Baker, 2012).

Attachment and relationship with parents

Different studies report exposure to parental alienation in children of divorce can influence the type of attachment these children develop in adulthood, as well as negatively affect the relationship with their parents (Baker & Ben-Ami, 2011; Baker & Verrocchio, 2013; Ben-Ami & Baker, 2012; Rowen & Emery, 2019). Thus, the negative effects of parental alienation extend into the type of attachment, different research suggesting higher rates of insecure attachment found in this type of subject (Baker & Ben-Ami, 2011; Ben-Ami & Baker, 2012). However, Baker and Verrocchio (2013) find no statistically significant link between exposure to parental alienation strategies in divorced families and children’s attachment style in adulthood. Concerning the relationship with parents, a denigration campaign by both parents was linked to a poor relationship between parents and child, with the latter feeling less emotionally close to the parent engaging in denigration than to the target parent (Rowen & Emery, 2019). Similarly, Godbout and Parent (2012) report a worsening relationship between those exposed to PA with the alienating parent, either temporarily or over a period of time, once there is a greater understanding of the parental alienation they have lived through.

Feelings on parental divorce, divorce, and alienating behaviors

Two studies reference adult children’s feelings and perceptions of parental divorce, their own experience of divorce, and the extent of parental alienation on their own children. In Rowen and Emery’s research (2019), adult children of divorced families report painful feelings about divorce, loss, abandonment, and increased propensity to see life through the divorce filter. These authors highlight that following a denigration campaign against either parent, children blamed the parent engaging in this action for the divorce. Baker (2005) states that one of the most tragic consequences of PA is that adults alienated in childhood repeat this behavior with their own children. He argues that this can be engaged in either by the romantic partner (men report marrying women with a generally narcissistic personality structure, similar to the alienating parent) or by their own parents (two participants reported that their children had been alienated by their mothers-their children´s grandmother). The author also reports higher divorce rates among adults exposed to PA during childhood, often due to lack of trust and intimacy with their partners and their own substance abuse problems and depressive symptoms.

Life satisfaction and quality

PA exposure causes significant impairment in many areas of children’s functioning, leading to reduced well-being during adulthood. Results by Verrocchio et al. (2019) showed this exposure linked to lower life quality. In particular, for adults who have suffered the separation of their parents, perceiving exposure to ABs during childhood increased the odds of decreased social functioning (SF) and general health (GH). They reported poor personal health that could worsen as well as interference in social activities due to physical and emotional problems.

Perception of emotional consequences

One qualitative study describes adult children’s perceptions of parental alienation and its consequences. In this research, Godbout and Parent (2012) indicate that these subjects report severe school difficulties, as well as internalizing (sadness, low self-esteem, anxiety and somatization) and externalizing symptoms (substance abuse in adolescence, hyperactivity and resistance to authority).

Discussion

According to the results of this systematic review, evidences of psychological consequences of exposure to PA during childhood in adult children is found. Therefore, it is essential that both mental health professionals and legal operators are aware of this phenomenon and the severity of its effects in order to put in place mechanisms for prevention and protection of minors against such conduct, as well as developing and offering a proper intervention strategy at the psychological level.

The reviewed articles’ results indicate a larger presence of psychopathological indicators during adulthood in individuals who experienced parental alienation during childhood. Research reports a greater probability of complying criteria for Major Depression and, therefore, of depressive episodes in this population. Moreover, finding no consensus on substance abuse or consumption, although some studies report a statistically significant relationship between this variable and PA. Due to the absence of research that only includes individuals of divorced parents in the study of the anxiety variable, the presence of anxiety in these individuals can only be reported from the data provided in a single quantitative methodology study, as well as for the narrations in these subjects in the qualitative methodology studies. In these studies, individuals report internalizing symptoms like sadness, low self-esteem, anxiety and somatization; and externalizing, substance abuse in adolescence, hyperactivity, and resistance to authority figures.

Several studies realized in children and adolescents on psychopathological variables linked to parental alienation report similar results to those offered in adulthood. Johnston et al. (2005) state that alienated children have more clinically serious behavioral problems, including depression, withdrawal, somatic complaints, and aggression. Other authors, such as Lowenstein (2007) and Stahl (1999) identify separation anxiety, panic attacks, phobias, depression, suicide attempts, sleep and eating disorders, obsessive–compulsive behaviors, and drug abuse in these children. In adolescence, a greater prevalence of PA associated generalized anxiety disorder is also reported (Hale et al., 2006). Results appear to indicate prolongation or extension of symptomatology of these subjects from childhood to adulthood. It is necessary to corroborate this hypothesis by performing longitudinal research, in addition to expanding the study of psychopathological variables present in childhood and adolescence in the period of adulthood.

Parental alienation appears to affect the relationship between adults and their parents, partner and own children. Some research indicates these individuals develop an insecure attachment style, with discrepancies found among studies when determining whether parental alienation influences the style of interpersonal relationship developed by children during adulthood. Likewise, it appears that exposure to PA may entail a repetition of this phenomenon toward their own children through the figure of their partner, which would indicate that when looking for a romantic partner, they seek a personality pattern similar to the alienating parent. This repetition can occur through the parents themselves, who are now grandparents (Baker, 2005). Higher divorce rates are reported among these adults because of psychopathology and personal factors, such as lack of trust and intimacy with their partners. As for the relationship with their parents, a worse relationship with the alienating parent is shown temporarily or for a longer period once they understand what PA actually entailed (Godbout & Parent, 2012; Rowen & Emery, 2019).

As regards personal variables adults who have suffered parental separation in childhood, perceive that exposure to PA negatively affected both their general health and social functioning, suffering interference in social activities due to physical and emotional problems. Self-esteem also seems to be affected by painful feelings about the divorce, feelings of loss and abandonment, internalizing hatred towards the target parent, guilt and self-hatred caused by their rejection of the parent, and a greater propensity to see life through the filter of divorce. Low self-esteem is closely linked to the individual’s self-efficacy, reflected both in poor employment prospects and low education level. These results reflect those in research with children, where among others, minors had difficulties in social relationships, coping deficits, difficulty modulating emotional states, low or defensively high self-esteem, low self-confidence, school difficulties, self-hatred, guilt, mistrust, fear of not feeling loved, pseudo-maturity, and feeling of abandonment (Fidler & Bala, 2010; Johnston et al., 2005; Lowenstein, 2006). The child experiencing PA loses both the ability to trust their own feelings and cognition, sense of reality and self-concept, depending entirely on the alienating parent (Boch-Galhau & Kodjoe, 2006). This loss of identity and submission to the pressures of adaptation and loyalty towards the parent could cause the aforementioned consequences in adulthood.

Limitations

Some limitations at both methodological and conceptual levels were identified. From a methodological point of view, the limited number of articles identified during the search procedure and the nature of the methodology used in this research, preventing comparison of results. Thus, meta-analysis had to be ruled out due to the small number of studies that were the object of the systematic review which did not guarantee an adequate statistical power. Secondly, selected studies come mainly from the USA and Italy, and we found cultural differences to other countries when extrapolating results; study sample is not delimited to children of divorced parents, with samples of subjects with divorced parents and intact families found; thus, results are not generalizable to this specific population. Likewise, language bias must be mentioned (as only English and Spanish language studies were included), and the heterogeneity of the psychopathological variables studied and the instruments used to measure them. Publication bias should be mentioned as an inherent limitation of systematic reviews. Thus, there may have been studies that were not included by both the eligibility criteria and search strategy implemented. One potential consequence associated with our inclusion criteria is that we do not consider publications that have not considered, at least, a measure of psychopathological or emotional well-being variable.

Likewise, it is difficult to establish the cause and effect of the long-term consequences of parental alienation in children of divorced parents due to the methodology used in the articles, since none of them is carried out in a controlled research context, such as a controlled longitudinal study. As all of these are retrospective studies, adults participants answer on their past perceptions and memories of the parental relationship during and after divorce in childhood, being able to see these affected, either blocking out information or having gaps in memory, or providing flawed information (suggestion, wrong attribution, or false memories). Therefore, some adults may have difficulty recalling parent’s perceptions and attributing the most appropriate emotion to the experiences of PA. According to the literature, when these experiences occur at an early age, the child cannot provide meaning to these events, as they are outside their level of awareness. During adulthood, they may reinterpret abusive experiences in childhood. Godbout and Parent (2012) indicate that the process of PA recognition is gradual and linked both to the subject´s maturity and ability to recognize and discriminate between facts and opinions. Similarly, Darnall and Steinberg (2008) state that the reasons for the reunification of the minor with the rejected parent there are often due to external events (serious illness, another divorce, death of a family member and so forth), the individual´s maturity, rethinking of a previous irrational belief, and hormonal changes. From there, it follows that the account of the PA experience and its recognition depends on multiple factors, with research subjects differing in this regard. It is also possible that some individuals´ emotional states when the study was performed, could mediate PA experience, either because of excess or defect; or differences in self-reporting this alienation in subjects who have sought psychological therapy at some point in their lives.

Baker (2018) states that a clinician can conclude with great certainty that alienation is present in a family if there are four factors: (1) a previous positive relationship between the child and the now rejected father; (2) absence of abuse by the rejected parent; (3) use of alienating behavior by the favored parent; and (4) presence of behavioral manifestations of alienation in the child. However, some of the studies analyzed does not detail whether the second factor is considered when talking about parental alienation in these subjects. Perhaps there are other reasons for the child’s rejection of one of the parents, which are essential when differentiating a process of parental alienation or estrangement (Bernet et al., 2020).

It is noteworthy that neither the Baker Strategy Questionnaire (BSQ) nor the Parental Alienation Syndrome Questionnaire (PASQ) used to categorize subjects with parental alienation include items in this regard, nor do they include variables that measure the quality of the relationship with the father objective before possible prior authorization or if there has been a refusal by that parent. Therefore, this information was completed in some studies using a demographic questionnaire (Reay, 2007). It should be noted that the involvement of the extended family or the environment of the alienating parents in the appearance or perpetuation of PA, a secondary but relevant aspect, is not evaluated in any of the measurement instruments. We also found an important gap when establishing a classification of severity of parental interference and its connection with adult children’s emotional consequences since we did not find any research that establishes criteria to differentiate the intensity of PA. Likewise, the family dynamics and family characteristics that allow us to contextualize PA’s experiences are also unknown.

Implications

As a practical implication of our study, knowing the emotional implications caused by exposure to alienation in children in the long-term is necessary to recognize the magnitude of this problem and identify the need for early therapeutic interventions in these families. In this sense, the Parenting Coordinator (PC) figure is necessary to intervene in this type of case. The practice of parental coordination requires the acquisition and application of specialized psychological knowledge to implement their role effectively. Their intervention aims to help parents implement and comply with court orders or parenting plans, make timely decisions regarding consistency with children’s psychological and developmental needs, reduce the number of harmful conflicts among the adults who care for the children to whom they are exposed and to decrease the pattern of unnecessary new litigation over child-related issues (APA, 2012).

At the policy level, the results of our study reinforce the need for the effective implementation of this therapeutic figure in Family Courts in order to protect minors from the serious short, medium and long-term consequences that the post-divorce interparental conflict can cause. Currently, in Spain, this figure is beginning to be implemented as a recommendation measure by forensic psychologists who carry out the evaluation in cases of custody of minors.

Future research should address these limitations since greater knowledge would help us to know more precisely and extensively the implications of exposure to behaviors of parental alienation on the lives of children throughout their development. Knowing the personal and psychopathological characteristics of parents, development and measures agreed in the judicial procedure, as well as the existence of intra-family maltreatment or child abuse, are essential factors in identifying problems and understanding family and psychological processes derived from these situations. It is necessary to develop parental interference measures to understand the severity of these behaviors and establish outcome criteria to see if parental alienation results from these. As for studying the effects of these behaviors on children in adulthood, it would be interesting to extend this to their relationships with partners and relational dynamics with the extended family as well as with their own children.

Conclusion

This study provides information on the state of research on the emotional and life consequences of adults exposed to Parental Alienation (PA) by their divorced parents during childhood and adolescence. From these studies, it appears that children exposed to this phenomenon report anxiety and depressive symptoms during adulthood, a greater risk of some type of psychopathology, lower self-esteem and self-sufficiency, higher rates of alcohol and drug consumption, and affected relationships as a couple and with the parents themselves, insecure attachment, lower life quality, higher divorce rates, feelings of loss, abandonment and guilt, and repetition of alienation behaviors on their own children by their new partner or grandparents. Due to the limited number of articles and limitations found in the research, more research is needed to offer more specific information to legal operators on this family dynamic and carry out preventive and promotion of mental health, as well as better treatment and psychological care for these families.

Data availability

The articles reviewed in this systematic analysis are included in references with an asterisk.

References

-

American Psychological Association. (2012). Guidelines for the Practice of Parenting Coordination. American Psychologist, 67(1), 63–71. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0024646

-

Armsden, G., & Greenberg, M. (1987). The Inventory of Parent and Peer Attachment: Individual differences and their relationship to psychological well-being in adolescence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 16, 427–454. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02202939

-

Baker, A. (2005). The Long-Term Effects of Parental Alienation on Adult Children: A Qualitative Research Study. The American Journal of Family Therapy, 33(4), 289–302. https://doi.org/10.1080/01926180590962129

-

Baker, A. (2018). Reliability and validity of the four-factor model of parental alienation. Journal of Family Therapy. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-6427.12253

-

Baker, A., & Ben-Ami, N. (2011). To Turn a Child Against a Parent Is To Turn a Child Against Himself: The Direct and Indirect Effects of Exposure to Parental Alienation Strategies on Self-Esteem and Well-Being. Journal of Divorce & Remarriage, 52, 472–489. https://doi.org/10.1080/10502556.2011.609424

-

Baker, A., & Chambers, J. (2011). Adult recall of childhood exposure to parental conflict: Unpacking the black box of parental alienation. Journal of Divorce & Remarriage, 52(1), 55–76.

-

Baker, A., & Festinger, T. (2011). Adult recall of childhood psychological maltreatment: A comparison of five scales. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment, and Trauma, 20, 70–89.

-

Baker, A., & Verrocchio, M. C. (2013). Italian College Student-Reported Childhood Exposure to Parental Alienation: Correlates With Well-Being. Journal of Divorce & Remarriage, 54, 609–628. https://doi.org/10.1080/10502556.2013.837714

-

Baker, A., & Verrocchio, M. C. (2015). Parental Bonding and Parental Alienation as Correlates of Psychological Maltreatment in Adults in Intact and Non-intact Families. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 24, 3047–3057. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-014-0108-0

-

Baker, A., & Verrocchio, M. C. (2016). Exposure to Parental Alienation and Subsequent Anxiety and Depression in Italian Adults. The American Journal of Family Therapy, 44(5), 255–271. https://doi.org/10.1080/01926187.2016.1230480

-

Balmer, S., Matthewson, M., & Haines, J. (2017). Parental alienation: Targeted parent perspective. Australian Journal of Psychology, 70(1), 91–99. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajpy.12159

-

Bartholomew, K., & Horowitz, L. (1991). Attachment styles among young adults: A test of a four-category model. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 61, 226–244.

-

Bech, P., Olsen, L., Kjoller, M., & Rasmussen, N. (2003). Measuring well-being rather than the absence of distress symptoms: A comparison of the SF-36 mental health subscale and the WHO-five well-being scale. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatry Research. https://doi.org/10.1002/mpr.145

-

Beck, A., Steer, R., & Brown, G. (1996). Manual for the Beck Depression Inventory – (BDI-II) (2nd ed.). Psychological Corporation.

-

-

Ben-Ami, N., & Baker, A. J. L. (2012). The long-term correlates of childhood exposure to parental alienation on adult self-sufficiency and well-being. American Journal of Family Therapy, 40(2), 169–183. https://doi.org/10.1080/01926187.2011.601206

-

Bernet, M. D., Baker, A., & Verrocchio, M. C. (2015). Symptom Checklist-90-Revised Scores in Adult Children Exposed to Alienating Behaviors: An Italian Sample. Journal of Forensic Sciences, 60(2), 357–362. https://doi.org/10.1111/1556-4029.12681

-

Bernet, W., Gregory, N., Rohner, R. P., & Reay, K. M. (2020). Measuring the Difference Between Parental Alienation and Parental Estrangement: The PARQ-Gap*. Journal of Forensic Sciences. https://doi.org/10.1111/1556-4029.14300

-

Boch-Galhau, W. V., & Kodjoe, U. (2006). Psychological consequences of PAS indoctrination for adult children of divorce and the effects of alienation parents. In R. Gardner & R Sauber y D. Lorandos (Eds.), The international handbook of parental alienation síndrome: conceptual, clinical and legal considerations (pp. 310–322). Springfield, Illinois: Charles C. Thomas Publisher LTD.

-

Bodenmann, G. (2005). Dyadic coping and its significant for marital functioning. In T. Revenson, K. Kayser, & G. Bodenmann (Eds.), Couples coping with stress: Emerging perspectives on dyadic coping (pp. 33–50). American Psychological Association.

-

Boszormenyi-Nagy, I., & Spark, G. (1973). Invisible Loyalties. Harper & Row.

-

Buchanan, C. M., & Waizenhofer, R. (2016). The Impact of Interparental Conflict on Adolescent Children: Considerations of Family Systems and Family Structure. In A. Booth, A. C. Crouter, M. L. Clements, & T. Boone-Holladay (Eds.), Couples in Conflict (pp. 246–262). Routledge.

-

Camisasca, E., Miragoli, S., Di Blasio, P., & Feinberg, M. (2019). Co-parenting Mediates the Influence of Marital Satisfaction on Child Adjustment: The Conditional Indirect Effect by Parental Empathy. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 28(2), 519–530. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-018-1271-5

-

Cloninger, C., Przybeck, T., Svrakic, D., & Wetzel, R. (1994). The Temperament and Character Inventory (TCI): A guide to its development and use. Center for Psychobiology and Personality, Washington University.

-

Cummings, E., & Davies, P. T. (2010). Marital conflict and children: An emotional security perspective. New York, NY: Guilford.

-

Cummings, E., Goeke-Morey, C., & Papp, L. M. (2016). Couple Conflict, Children, and Families: It’s Not Just You and Me, Babe. In A. Booth, A. C. Crouter, M. L. Clements, & T. Boone-Holladay (Eds.), Couples in Conflict (pp. 201–245). New York, NY: Routledge.

-

Darnall, D., & Steinberg, B. F. (2008). Motivational Models for Spontaneous Reunification With the Alienated Child: Part II. The American Journal of Family Therapy, 36(3), 253–261. https://doi.org/10.1080/01926180701643230

-

Davison, M., Bershadsky, B., Bieber, J., Silversmith, D., Maruish, M., & Kane, R. (1997). Development of a brief, multidimensional, self-report instrument for treatment outcomes assessment in psychiatric settings: Preliminary findings. Assessment, 4, 259–276.

-

Derogatis, L., Lipman, R., & Covi, L. (1973). SCL-90: An outpatient psychiatric rating scale – preliminary report. Psychopharmacology Bulletin, 9, 13–27.

-

Derogatis, L. (1977). SCL–90–R Administration, scoring and procedures manual I for the revised version. Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine.

-

Diener, E., Emmons, R., Larsen, R., & Griffin, S. (1985). The Satisfaction With Life Scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 49, 71–75. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327752jpa4901_13

-

Ewing, J. A. (1984). Detecting alcoholism: The CAGE questionnaire. Journal of the American Medical Association, 252, 1905–1907.

-

Fidler, B. J., & Bala, N. (2010). Children resisting postseparation contact with a parent: Concepts, controversies, and conundrums. Family Court Review, 48(1), 10–47. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-1617.2009.01287.x

-

Furman, W., & Buhrmester, D. (1985). Children’s perceptions of the personal relationships in their social networks. Developmental Psychology, 21, 1016–1024.

-

Gardner, R. (1992). The parental alienation syndrome, A guide for mental health and legal professionals. Cresskill, NY: Creative Therapeutics.

-

Gardner, R. (2006). The Parental Alienation Syndrome and the corruptive power of anger. In R. Gardner, R. Sauber, & D. Lorandos (Eds.), The International Handbook of Parental Alienation Syndrome: Conceptual, Clinical and Legal Considerations (pp. 33–49). Charles C. Thomas Publisher.

-

Godbout, E., & Parent, C. (2012). The Life Paths and Lived Experiences of Adults Who Have Experienced Parental Alienation: A Retrospective Study. Journal of Divorce & Remarriage, 53(1), 34–54. https://doi.org/10.1080/10502556.2012.635967

-

González, I. (2019). Las interferencias parentales y la alienación parental: encuesta a profesionales. In A. M. Pérez & y M. P. Antón (Eds.), Estudio multidisciplinar sobre interferencias parentales (pp. 127–160). Madrid, España: Dykinson S.L.

-

Grych, J., Seid, M., & Fincham, F. (1992). Assessing marital conflict from the child’s perspective: The children’s perception of interparental conflict scale. Child Development, 63, 558–572. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.1992.tb01646.x

-

Hale, W. W., Engels, R., & Meeus, W. (2006). Adolescent’s perceptions of parenting behaviours and its relationship to adolescent Generalized Anxiety Disorder symptoms. Journal of Adolescence, 29(3), 407–417. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2005.08.002

-

Harman, J., & Biringen, Z. (2016). Parents acting badly: How institutions and societies promote the alienation of children from their loving families. Fort Collins.

-

Harman, J., Kruk, E., & Hines, D. (2018). Parental Alienating Behaviors: An Unacknowledged Form of Family Violence. Psychological Bulletin: American Psychology Association, 144(12), 1275–1299. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000175

-

Harman, J., Leder-Elderb, S., & Biringen, Z. (2019). Prevalence of adults who are the targets of parental alienating behaviors and their impact. Children and Youth Services Review, 106, 1–13.

-

Johnston, J. R. (2003). Parental Alignments and Rejection: An Empirical Study of Alienation in Children of Divorce. Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law, 31(2), 158–170.

-

Johnston, J. R. (2005). Children of divorce who reject a parent and refuse visitation: Recent research and social policy implications for the alienated child. Family Law Quarterly, 38(4), 757–775.

-

Johnston, J. R., & Campbell, L. E. (1988). Impasses of divorce: The dynamics and resolution of family conflict. Free Press.

-

Johnston, J. R., Walters, M. G., & Olensen, N. W. (2005). The Psychological Functioning of Alienated Children in Custody Disputing Families: An Exploratory Study. American Journal of Forensic Psychology, 23(3), 39–64.

-

Kelly, J. B., & Johnston, J. R. (2001). The alienated child: A reformulation of parental alienation syndrome. Family Court Review, 39(3), 249–266. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.174-1617.2001.tb00609.x

-

Klass, J., & Klass, J. V. (2005). Threatened Mother Syndrome (TMS): A Diverging Concept of Parental Alienation Syndrome (PAS). American Journal of Family Law, 18(4), 189–191.

-

Laumann-Billings, L., & Emery, R. (2000). Distress among young adults from divorced families. Journal of Family Psychology, 14, 671–687. https://doi.org/10.1037/0893-3200.14.4.671

-

Lowenstein, L. F. (2006). The psychological effects and treatment of the Parental Alienation Syndrome. In R. Gardner, R. Sauber, & y D. Lorandos (Eds.), The international handbook of parental alienation syndrome : conceptual, clinical and legal considerations (pp. 292–301). Springfield, Illinois: Charles C. Thomas Publisher LTD.

-

Lowenstein, L. F. (2007). Parental alienation: How to understand and address parental alienation resulting from acrimonious divorce or separation. Russell House Publishing.

-

Machuca, L. (2005). Parental alienation syndrome: Perceptions of parental behaviors and attitudes in divorced vs. non-divorced families. (Dissertation). Anchorage, Alaska: University of Alaska.

-

Martínez-Pampliega, A., Aguado, V., Corral, S., Cormenzana, S., Merino, L., & Iriarte, L. (2015). Protecting Children After a Divorce: Efficacy of Egokitzen—An Intervention Program for Parents on Children’s Adjustment. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 24(12), 3782–3792. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-015-0186-7

-

Maturana, S. L., Matthewson, M., Dwan, C., & Norris, K. (2018). Characteristics and experiences of targeted parents of parental alienation from their own perspective: A systematic literature review. Australian Journal of Psychology, 1-9. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajpy.12226

-

Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., & Altman, D. G. (2009). Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.06.005

-

Moran, J. A., Sullivan, T., & Sullivan, M. (2015). Overcoming the Co-Parenting Trap: Essential Parenting Skills When a Child Resist a Parent. Overcoming Barriers Inc.

-

Parker, G., Tupling, H., & Brown, L. (1979). A parental bonding instrument. British Journal of Medical Psychology, 52, 1–10.

-

Reay, K. (2007). Psychological distress among adult children of divorce who perceive experiencing parental alienation syndrome in early years (Dissertation). Capella University.

-

Radloff, L. (1977). The CES-D Scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement, 1, 385–401. https://doi.org/10.1177/014662167700100306

-

Rosenberg, M. (1965). Society and the adolescent self-image. Princeton University Press.

-

Rowen, J., & Emery, R. (2014). Parental denigration: Examining the deliberate denigration of co-parents as reported by young adults and its association with parent–child closeness. Couple and Family Psychology: Research and Practice, 3, 165–177.

-

Rowen, J., & Emery, R. E. (2019). Parental denigration boomerangs versus alienates: Parent–child closeness, reciprocity, and well‐being using multiple informants. Family Relations: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Applied Family Studies, 68(1), 119–134. https://doi.org/10.1111/fare.12324

-

Sher, L. (2015). Parental alienation and suicide in men. Psychiatria Danubina, 27, 288–289. 2015–46818–013.

-

Spielberger, C., Gorsuch, R., & Lushene, R. (1970). Manual for the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory. Consulting Psychologists Press.

-

Stahl, P. M. (1999). Alienation and alignment of children. In P. M. Stahl (Ed.), Complex Issues in Child Custody Evaluations (pp. 1–25). SAGE Publications.

-

Steinberg, L., Lamborn, S., Dornbusch, S., & Darling, N. (1992). Impact of parenting practices on adolescent achievement: Authoritative parenting, school involvement, and encouragement to succeed. Child Development, 63, 1266–1281. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.1992.tb01694.x

-

Stoner-Moskowitz, J. (1998). The Effect of Parental Alienation Syndrome and Interparental Conflict on the Self-concept of Children of Divorce. Miami, FL: Caribbean Center for Advanced Studies.

-

Sturge-Apple, M. L., Skibo, M., & Davies, P. T. (2012). Impact of Parental Conflict and Emotional Abuse on Children and Families. Partner Abuse, 3(3), 379–400. https://doi.org/10.1891/1946-6560.3.3.e8

-

Turkat, I. D. (2002). Parental Alienation Syndrome: A review of Critical Issues. Journal of the American Academy of Matrimonial Lawyers, 18, 131–176.

-

Verrocchio, M. C., Baker, A. J. L., & Bernet, W. (2016). Associations between exposure to alienating behaviors, anxiety, and depression in an Italian sample of adults. Journal of Forensic Science, 61(3), 692–698. https://doi.org/10.1111/1556-4029.13046

-

*Verrocchio, M. C., Marchetti, D., Carrozzino, D., Compare, A., & Fulcheri, M. (2019). Depression and quality of life in adults perceiving exposure to parental alienation behaviors. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 17. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-019-1080-6

-

*Verrocchio, M. C., Marchetti, D., & Fulcheri, M. (2015). Perceived Parental Functioning, Self-Esteem, and Psychological Distress in Adults Whose Parents are Separated/Divorced. Frontiers in Psychology. 6. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01760

-

Waldron, K. H., & Joanis, D. E. (1996). Understanding and collaboratively treating parental alienation syndrome. American Journal or Family Law, 10, 121–133.

-

Ware J. E., Gandek B., & the IQOLA Project Group. (1994). The SF-36 health survey: Development and use in mental health research and the IQOLA Project. International Journal of Mental Health, 23, 49–73.

-

Wishman, M. A. (2001). The associationbetween depression and marital dis-satisfaction. In S. R. H. Beach (Ed.), Marital and family processes in depres-sion: A scientific foundation for clinicalpractice. American Psychological Association.

-

Zemp, M., Bodenmann, G., & Cummings, E. M. (2016). The significance of interparental conflict for children. European Psychologist, 21(2), 99–108. https://doi.org/10.1027/1016-9040/a000245

-

Zimmerman, M., & Coryell, W. (1987). The Inventory to Diagnose Depression, lifetime version. Acta Psychiatrica Scandanavia, 75, 495–499.

Funding

Open Access funding provided thanks to the CRUE-CSIC agreement with Springer Nature.

-